It’s hard to know when to take NASA seriously anymore. In the past, if the big brains at the space agency said we were going to the moon, well, pack your bags, because we’re shipping out. These days? Not so much. As TIME has noted, one of the best ways to tell if any planned mission described in any NASA press release has a chance of actually flying is to use the Count the Conditionals Rule. The greater the number of references to what a spacecraft could achieve or when it should be flying, the less chance it’s going anywhere at all.

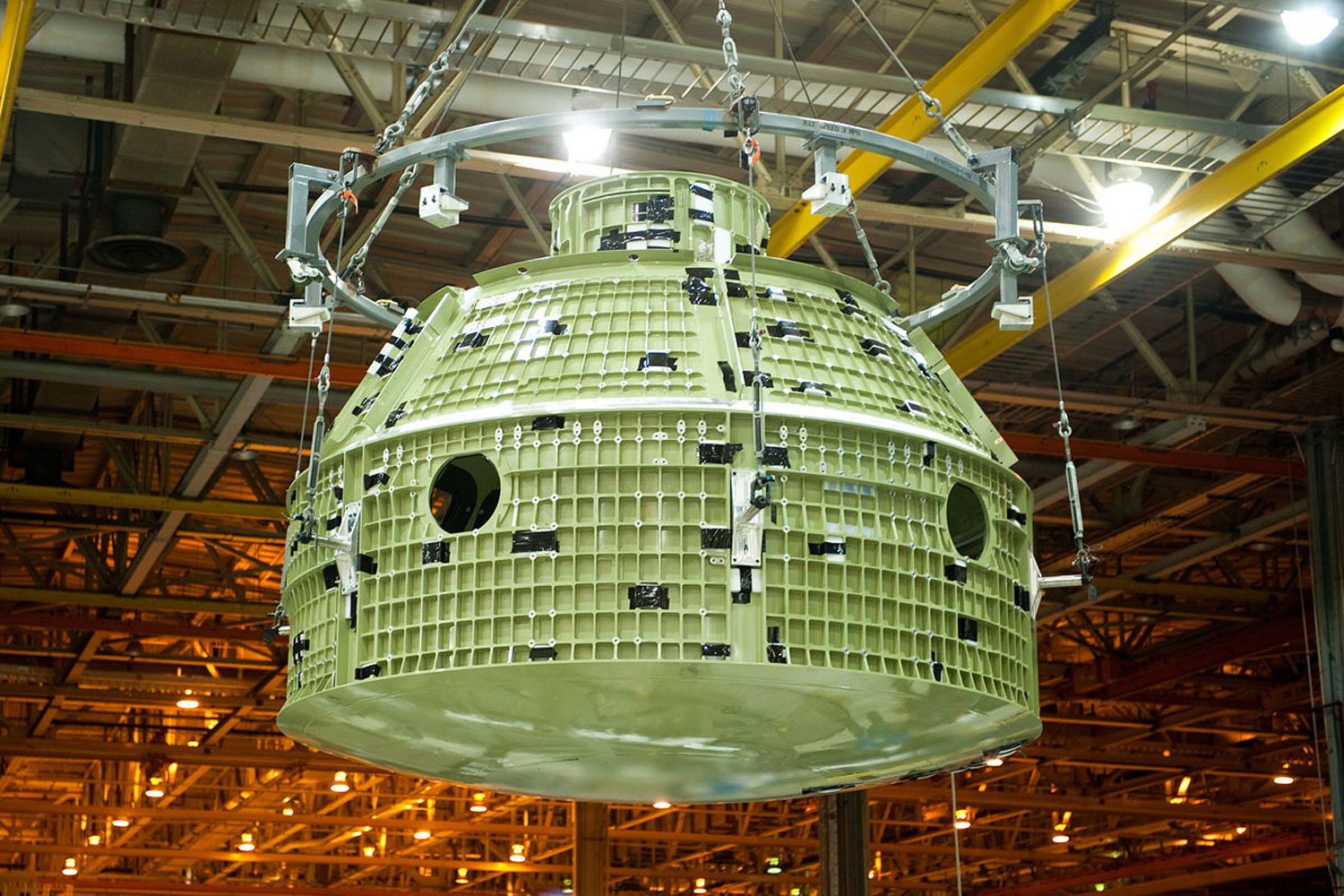

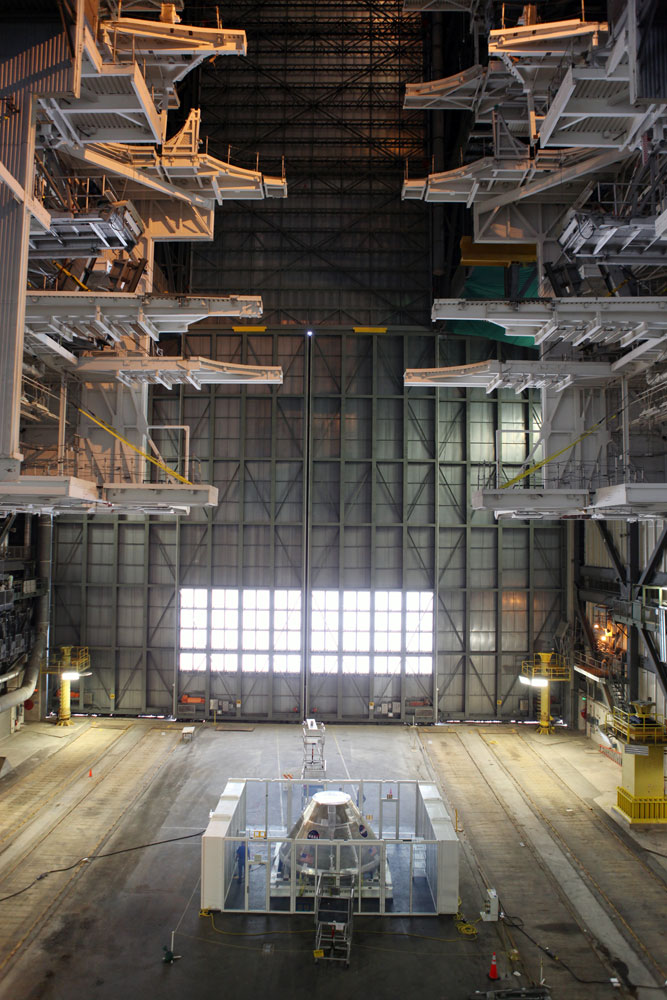

For years now, the manned space program has been drowning in conditionals. We were building spacecraft that could take humans to Mars—then we weren’t; we were committing ourselves to a new program that would have us back on the moon by 2015—and then we broke the commitment. But slowly, the manned program appears to be getting back on track. Real hardware is being built again, real firing tests are being conducted, and a first test launch of a new deep-space vehicle is scheduled for September. If (and that’s a planet-sized if), funding stays in place, White House policy doesn’t change and general fecklessness doesn’t prevail, the U.S. could at last be finding its way back to its once-dominant role in space.

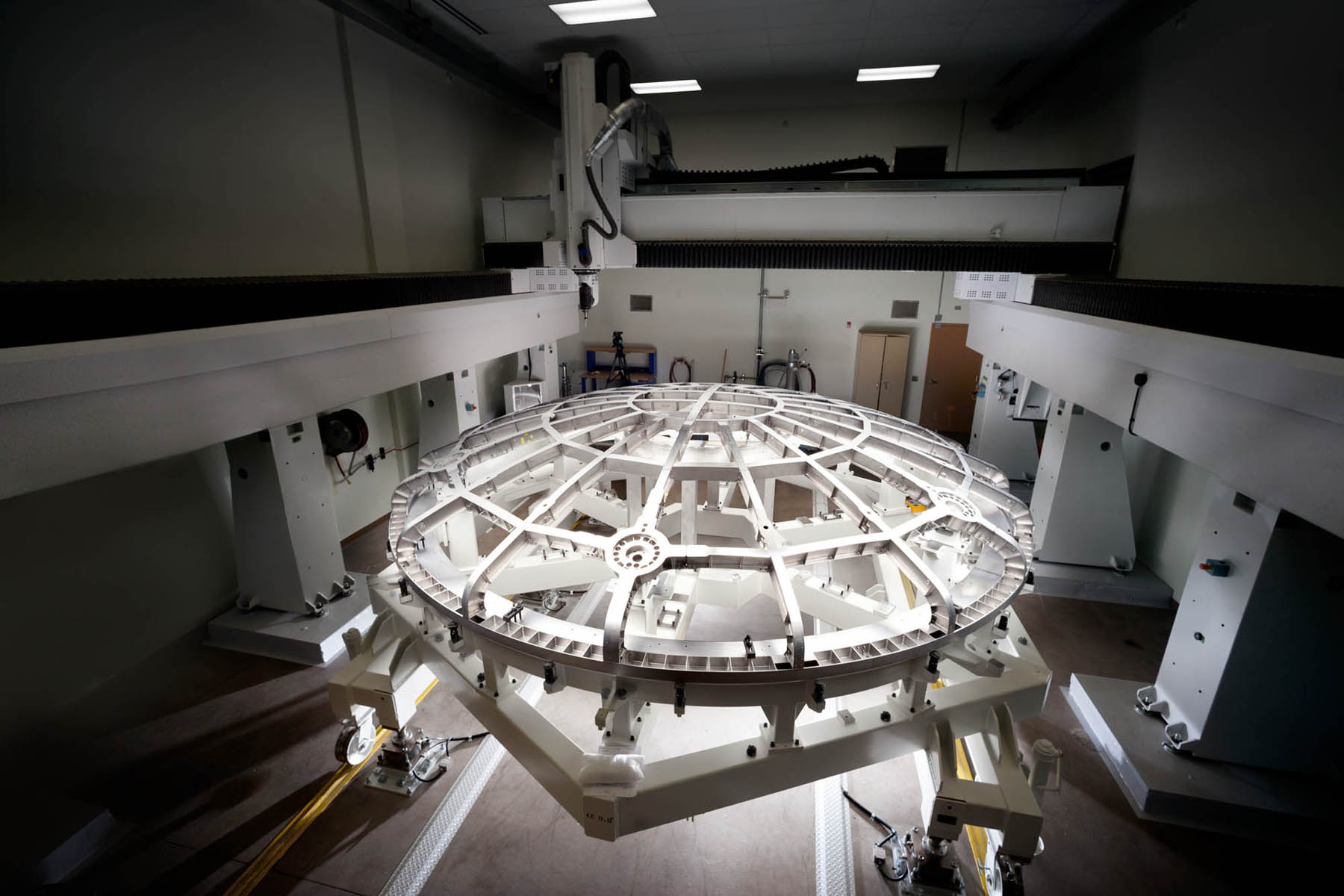

NASA is making its current push with two new machines: a crew vehicle dubbed Orion and a rocket that is better known better by its acronym—SLS—than by it’s decidedly prosaic name, which is Space Launch System. But anything the machines lack in marketing sizzle they make up in engineering ambition. (Continued below gallery)

PHOTOS: A Look at America's Next Space Machines

Orion’s design DNA runs straight back to the old Apollo spacecraft—which is a very good bloodline. Like the Apollos, it’s a two-part ship, with a conical command module that houses the astronauts, and a cylindrical service module for batteries, oxygen, fuel cells, engine and more. The Apollos’ 210 cu. ft. (5.9 cu. m) habitable space accommodated three astronauts. Orion’s 316 cu. ft (8.9 cu. m) is designed for four. The crews will need that extra elbow room. The longest Apollo lunar mission, Apollo 17, lasted just 12 days, 13 hrs. In its current configuration, the Orion is intended for missions ranging from 21 to 210 days.

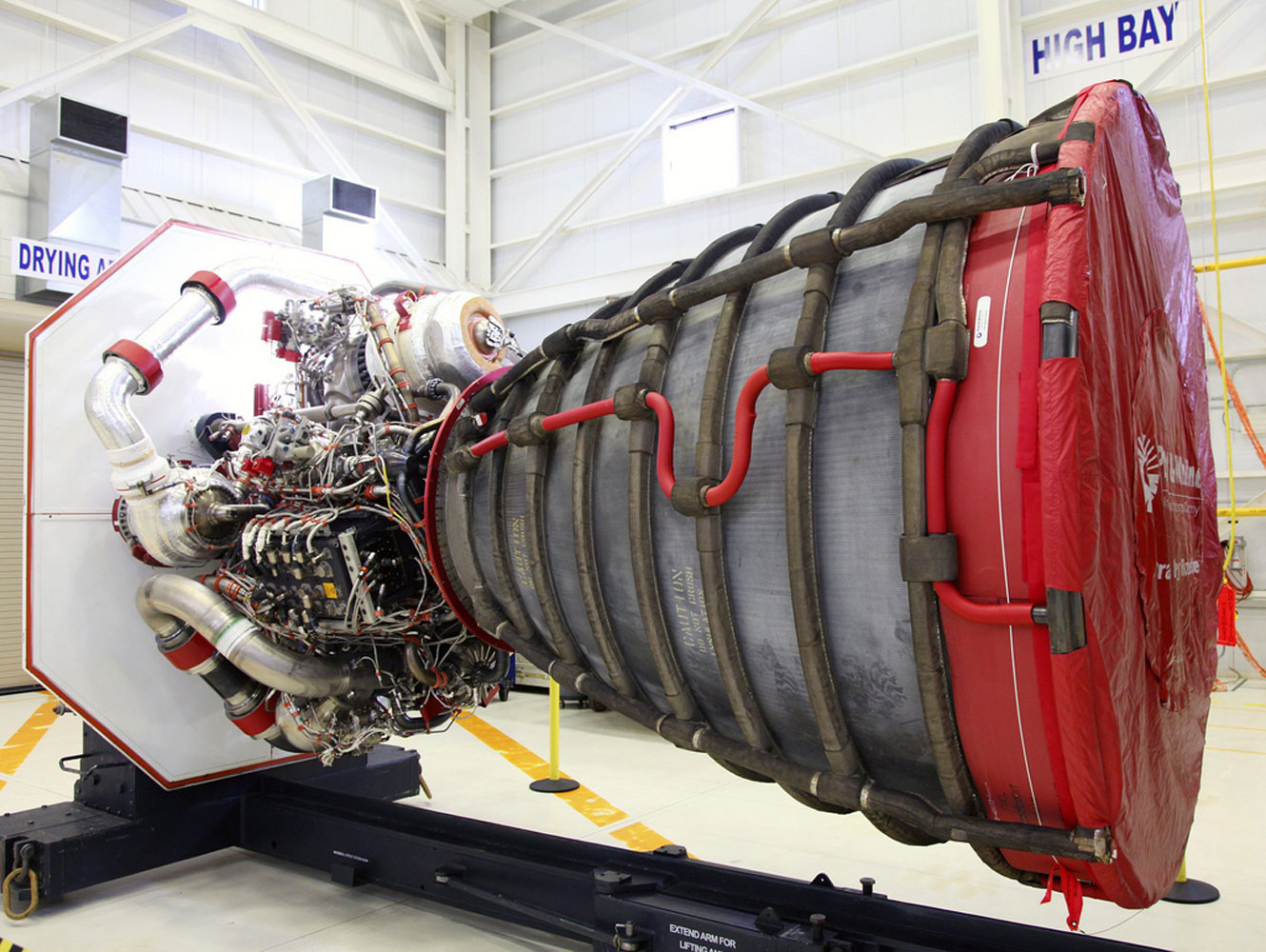

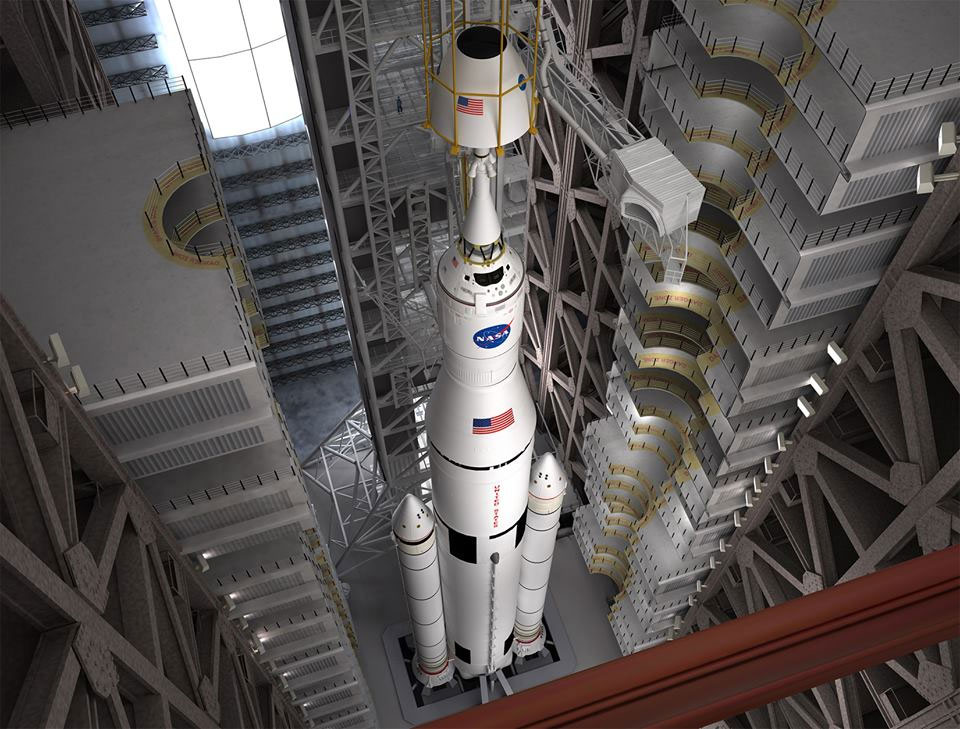

The SLS is similarly descended from earlier NASA hardware—both the shuttle and the Saturn V moon rocket. Its main stage engines are upgraded shuttle engines, and it carries strap-on solid boosters also based on the shuttle’s. The new rocket’s upper stage engines are based on the design of the old J-2 that powered the second and third stages of the Saturn. The SLS also gets its looks from the Saturn—a NASA nod to the public relations value of the new rocket conjuring up images of the biggest and best one the space agency ever built.

While the Orion comes in just one size, there will actually be two models of the SLS: one capable of lifting 70 metric tons (154,000 lbs, or 70,ooo kg) to low Earth orbit; and another than can loft 130 metric tons (286,000 lbs., or 130,000 kg). The smaller version will stand 321 ft. (98 m), just shy of the Saturn V’s 363 ft. (111 m). The bigger one will exceed its grandaddy’s stature, measuring 384 ft (117 m).

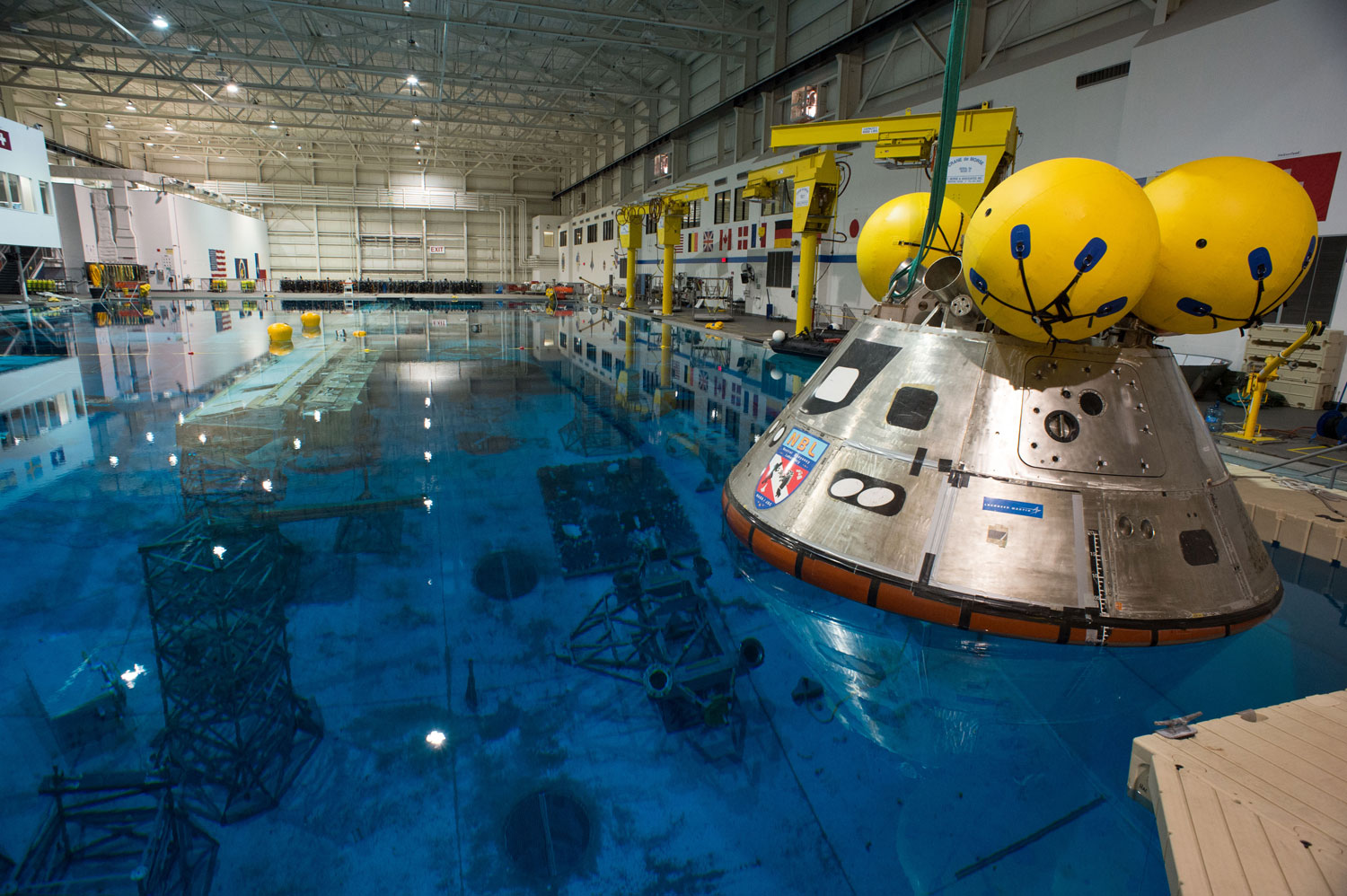

That, of course, is assuming any of this machinery ever sees a launch pad. At the moment, the outlook is best for Orion, which at least knows what it feels like to fly—a little. In 2010, the launch escape system—the small cluster of rockets that would lift the command module up and away from the SLS booster if a Challenger-type problem occurred during the early part of flight—was tested in White Sands, N.M. The motors took an Orion mock-up 6,000 ft. (1,828 m) high before a parachute descent.

(MORE: Chinese Social Media Prays for ‘Little Bunny’ Moon Rover)

This coming September, the Orion and a partially completed service module will fly in space for the first time atop a Delta heavy-lift rocket, setting out on a two-orbit flight around the Earth, 3,600 mi. (5,800 km) above the surface, or 15 times higher than the International Space Station. The purpose will be to test both the spacecraft and its heat shield as they re-enter the atmosphere at return-from-deep-space speeds of 20,000 mph (32,000 k/h) generating temperatures of 4,000º F (2,200º C). It ain’t a manned trip to the moon, but it’s a start.

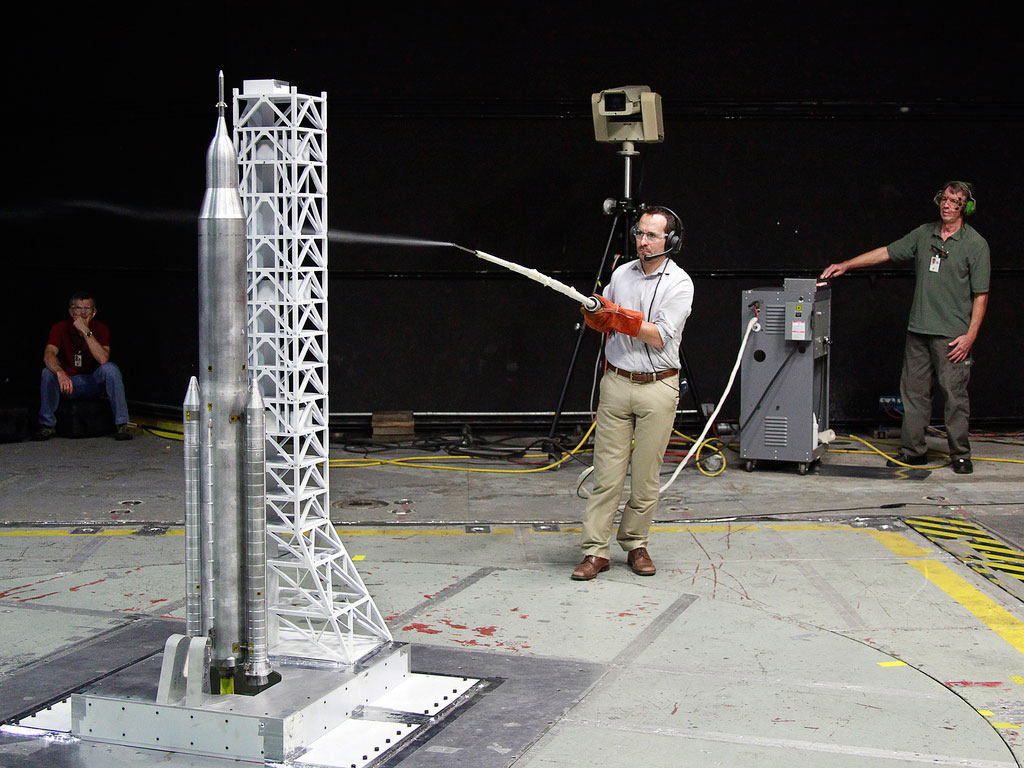

The SLS has a lot further to go. Engines have been fired, some basic shrouds and housings have been built, wind tunnel tests have taken place, but the pace has been slow—far slower than things went for the Saturn V in the turbocharged early years of the space race. The first flight of the rocket with an Orion spacecraft mated to it is not planned until 2017; the first crewed flight won’t happen until 2021 at the earliest. But no one pretends those dates can’t change. The recent budget deal Congress struck kept the program’s money spigot open and relieved worries for now that one more NASA program would fall victim to politics—something that has happened many times before. It was John Kennedy who launched the original moon program, Richard Nixon who killed it, George W. Bush who revived it and Barack Obama who killed it again. NASA directors are well aware of that body count.

At the moment, with the moon off the table, the missions the space agency is planning for the SLS and Orion are equal parts laughable and vague. First, we’ll fly out to an asteroid, capture it in a gigantic bag, tow it to the vicinity of the moon and then…you know…visit it. Really. Next we’ll go to Mars, a trip that NASA says will happen in 2030-something-something-but-really-before-2040. We’ll see.

In the mean time, if nothing else, the designers, engineers, chemists, metalworkers, builders, riveters, haulers and others who actually imagine and create the magnificent machines that have taken us far beyond Earth before and could once again, continue to do the only thing they can—which is keep to at it. The money, the will and the governmental vision may run out before they’re done, but for the moment at least, the work goes on.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com