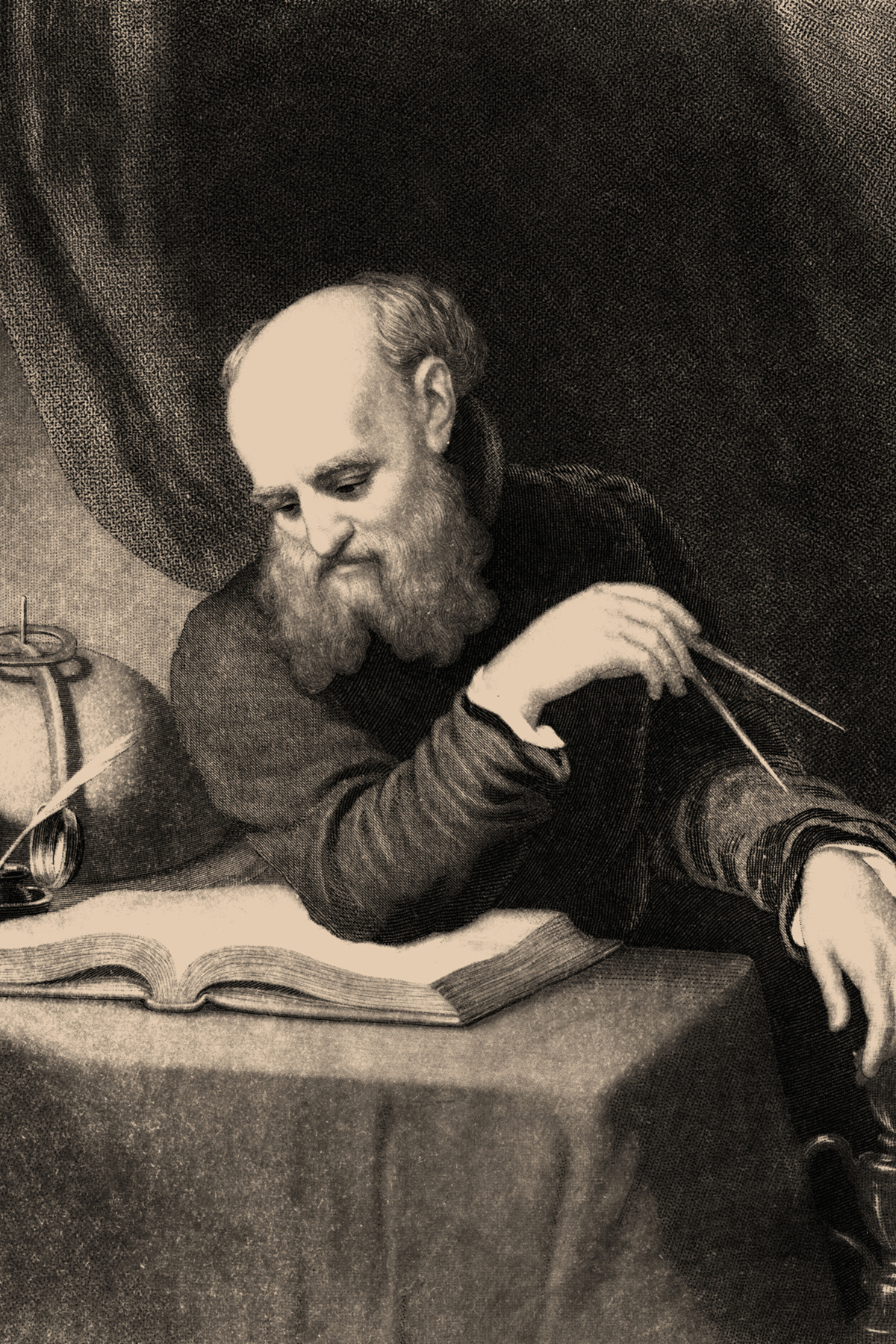

So here’s a fine howdy-do for Galileo Galilei: Exactly one day—one flipping day—after the great man’s 450th birthday, on Feb. 15, 2014, a study by the National Science Foundation (NSF) revealed that one in four Americans does not know that the Earth orbits the Sun. That’s roughly 78 million people, or six times greater than the entire population of Galileo’s native Italy in 1632—the year he was sentenced to life under house arrest for advancing that heretical belief. Yet somehow, four centuries later later, 25% of us still haven’t gotten the word. If there’s any comfort at all to be taken from the study—and there is, but only in that I’m-not-the-dumbest-one-in-the-class sort of way—it’s that the European Union fared even worse, with 36% flunking the heliocentrism part of the science test.

It’s a reassuring truth of human history that wisdom is eternal. Our greatest accomplishments and insights in art, science, technology, philosophy, theology, medicine and government are timeless—things that once known can never truly be unknown. But it’s an equally hard truth that stupid is forever too. The flat-earthers have always been with us, as have the believers in phrenology and alchemy and eugenics and sorcery, and, more recently and perniciously, the climate change deniers and the vaccines-cause-autism ninnies.

Sometimes it’s greed and political calculation at work: If we call climate change a hoax, we keep the riches flowing to the fossil fuel industry. Sometimes it’s a search for answers (if a child develop autism someone must be to blame) coupled with a know-nothing carnival barker like Jenny McCarthy. And sometimes it’s religion.

Galileo’s persecutors were the fathers of the Catholic Church, holding fast to a Bible that described the Earth as fixed and unmovable and the sun as rising and setting and returning to its place each day. The people who deny evolution today aren’t in the field, collecting the bones and offering reasoned alternatives to what Darwin discovered. They too know what they know because the Bible says—or seems to say—it’s true.

But to blame the believers is, in its own way, a blinkered view of things. The hard fact is, there are plenty of people—the majority of people, in fact—who can comfortably live in a world in which faith and science live side by side. It was Carl Sagan himself who once wondered why a God who presides over a universe in which evolution unfolds, in which physical sciences play out and in which great truths are slowly discovered by people with dawning wisdom, isn’t somehow a subtler, more nuanced and more appealing God.

The very same day the dispiriting NSF study was announced, Rice University released a far more encouraging survey of 10,000 scientists, evangelical Protestants and average Americans. According to the Rice results, almost 50% of Evangelicals believe that science and religion can work together, a figure that actually exceeds the 38% of all Americans who believe the same thing. As for all those non-spiritual scientists? Eighteen percent of them attend weekly religious services, only slightly less than the 20% of average Americans who are also regular worshippers. And 15% think of themselves as “very religious,” compared to 19% of everyone else. Scientists who also happen to be Evangelicals actually practice their religion more than Evangelical non-scientists.

Yes, there are some findings in the survey likely to give science types heartburn: 60% of Evangelicals believe that scientists should be willing to consider miracles as possible explanations for the phenomena they study, as do 38% of all Americans. But on the whole, the warring camps we hear so much about may be smaller and friendlier than we’ve come to believe. And to the extent that a battle does exist, it’s mostly being fought out at the extremes: the finger-in-the-eye atheists like Bill Maher, who regard believers with a kind of pitying disdain and don’t care who knows it; the religious fundamentalists who defy inquisitiveness, defy reason, demanding a literal interpretation of Scripture that includes a great flood and a 6,000 year old world and a planet full of fossils and billions-year-old rocks that are put there merely to test our faith.

In fairness, there is not a complete equivalency here. The likes of Maher may be tiresome, but they make a point: The world is 4.5 billion years old. Full stop. The Earth does revolve around the Sun—period. On these matters, the modern day fundamentalists are—how best to put this?—wrong. When the Catholic Church as long ago as 1758 lifted its ban on teaching the sun-centered solar system and in 1992 formally acknowledged error in its treatment of Galileo, the very guardians of Scripture themselves were acknowledging that simply because a verse is written in a book does not make it so. To insist otherwise is to fight a rearguard action, one that holds entire societies back.

Science has been with us since the beginning of time. Faith has been with us since we opened our eyes and began wondering what all that science and everything else around us means. By now, many eons on, we ought to have figured out a way to marry the two. Perhaps in another 450 years we will.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com