Happy World Water Week! Yes, it’s that time of year again, as water wonks who spend their worthy careers thinking about how to get more people access to clean H20 kick off meetings in Stockholm today. So as you kick back on your sprinkled lawn or float in your pool this Labor Day, spare a moment to consider water, the element that puts the ‘iced’ in that Long Island Iced Tea:

With water — as with so many things — geography is destiny. Depending on where we live, it’s something we are either condemned to think about all the time, or something we have the luxury to almost entirely ignore. Over the years, more than a few entrepreneurs have seen the $$$ in that schism, and much anxiety about water becoming the ‘blue gold’ of the 21st century has followed.

Water exports have been considered on both the sending and receiving end since the middle of last century, particularly between the U.S. and Canada, though no major international operations have yet to get underway. In places where there is some bilateral water trade, like Singapore’s import of Malaysian water, there is a push for greater water independence on the importing end.

But hope springs eternal. In July, a Texas-based company announced plans to start the ambitious venture of exporting water from Alaska to India. While politicians duke it out over whether or not to open up the Arctic regions of the 49th state to offshore oil drilling, Alaskans further south are ready and waiting to sell off their local resource. S2C Global Systems, which owns a 50% stake in the subsidiary Alaska Resource Management, intends to start shipping billions of gallons of fresh water from Blue Lake in Sitka, Alaska, to a coming-soon “World Water Hub” in India, from which water will then be shipped again to water-poor nations around the Arabian Sea.

What’s a World Water Hub? Good question. Basically, Alaska Resource Management plans to have water loaded directly from a large pipe on the glacially fed Blue Lake, which is also home to a deepwater port. From there, cargo ships would carry the water to an as-yet undisclosed location in India, where an awaiting tank system would be used to store the water and maintain the quality of the water for distribution to countries in the Middle East and north Africa that are constantly grappling with water shortages.

It would basically serve as an alternate to desalination — the process by which salt is extracted from sea water to make it potable. Desalination is already widely used in areas without a lot of water options and advocated by water management types, but some protest that the process, which is energy intensive, sucks up too many fossil fuels. But shipping does too – in spades. Add to that the fact that desalinized water is currently cheaper than the water that S2C reckons it will sell — plus the likelihood that someday Alaskans are going to wake up and realized they have sold off billions of gallons of their local lake at bargain basement prices — and the plan starts to get a little hazy.

Nevertheless, it has an extremely instructive point: most of the planet’s fresh water is located near the poles, and most of the planet’s human beings are located on the equator. That makes for an alarming scarcity of access to water on our blue planet, and it’s only going to get scarcer as the global population is fixing to increase up to 50% over the next 50 years. Over one billion people lack access to safe drinking water today. That’s one in every six people. About 4000 children die every day from water-borne diseases.

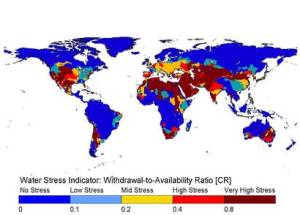

Here’s a graphic, courtesy of the World Water Council, that illustrates the correlation between location and water stress across the globe in 1999:

Courtesy of World Water Council

As climate change continues to deliver increasingly unpredictable rainfall and shrink glaciers whose meltwater is a lifeline to some of Asia’s most populous places, governments’ are going to have to start rethinking their approach to improving their populations’ water security. A study released today by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) outlines how the longstanding practice of relying on large dams to store water for drinking and for agriculture may not be the best option in this new era of uncertainty. Some 50,000 large dam have been built around the globe since the 1950s, displacing up to 80 million people and disrupting the lives of another 470 million who live downstream from dammed rivers.

IWMI suggests the better way to secure water supply, particularly for the rural poor who rely on rainfall for farming, is to develop combined systems of large and small-scale options like using water from wetlands, groundwater, and collecting rainfall in ponds, tanks and reservoirs. “Unless we can reduce crippling uncertainty in rainfed agriculture through better water storage, many farmers in developing countries will face a losing battle with a more hostile and unpredictable climate,” Matthew McCartney, the report’s lead author and a hydrologist at IWMI, said in a press release. IWMI estimates that some 500 million people across India and Africa would benefit with the simple, top-down restructuring of water resources that the report recommends.

Collecting groundwater, of course, not nearly as colorful a solution as a series of World Water Hubs. But improving local infrastructure for small scale farmers to manage their own water does offer them something that no privately owned water source ever could – a measure of control over their own destiny.

And if that’s not something to raise your glass to on Labor Day, I don’t know what is.