AP

Unruly winds were still spreading the fires late into the night on Thursday in San Bruno, California, after an explosion in the San Francisco satellite community set more than 50 homes on fire. People in the area thought they had witnessed a plane crash, hearing a loud rumbling and watching a fireball lift up into the afternoon sky. In fact, what they had very likely witnessed was a rupture on a natural gas pipeline. A few hours later, at least one person had been killed in the ensuing flames and police were scrambling to account for all the residents who had fled their homes.

Natural gas pipelines are all around us, stretching over 2 million miles throughout the country and providing a quarter of America’s energy. More than 650,000 miles of new pipeline were added in the U.S. between 1986 and 2004, according to the American Gas Association (AGA). Explosions in lines carrying the highly flammable methane-filled gas do happen, but the AGA says they are occurring less and less, citing a 28% decline in reportable incidents in that same 18-year period.

Still, the industry is growing. Not only does the cleaner-burning resource have a green edge over high-polluting coal, energy companies have figured out how to access uptapped reserves in beds of shale in recent years, and have been doing so at unprecedented rates. Shale gas production in the U.S. rose 71% between 2007 and 2008, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Meanwhile, environmental groups and residents near these new drilling operations have real concerns that the method being used to extract the gas may generate toxic wastewater and, worse, could cause groundwater pollution in their vicinities.

The process under fire is called hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” in which water, often mixed with sand and chemicals, is flushed at high pressures into rock beds to break them up and allow trapped gas to escape and be captured. The process has been around for years, developed for extracting oil and gas in the west, and is now spreading to new areas, many of which are closer to larger populations on the east coast. The technology is exempt from federal regulation under the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) despite the fact that several communities around the U.S. have reported drinking water contamination that they say is due to fracking near their homes. (The recent documentary “Gasland” tours the country looking at the problem.) Now, the EPA, which once determined that fracking posed no threat, is revisiting the issue (at Congress’ behest) in a new study. The EPA web site states that it “agrees with Congress that there are serious concerns from citizens and their representatives about hydraulic fracturing’s potential impact on drinking water, human health and the environment.”

Gas companies using hydraulic fracturing insist that it’s safe, but acknowledge that they will need to listen to residents’ concerns as they move ahead with planned expansions. A particularly hot debate is raging in Pennsylvania between the drills and the drill-nots who live above a gas-infused geologic structure called the Marcellus Shale. It’s a classic dilemma: the booming industry is supported by politicians who say that it brings much needed jobs and raises property values, but is opposed by residents who feel like their quality of life is being sacrificed at the expense of economic development.

Here’s an excerpt from NRDC’s Rob Perks’ blog about a group of folks in Dimock, Pennsylvania who are fighting back:

Some 15 families have filed a lawsuit against Cabot Oil and Gas, seeking to correct what they say are pollution problems caused by the company’s activities and to halt future drilling in the Marcellus Shale near their town. These faces of Dimock cite extensive damage, such as fish kills and contaminated drinking water from toxic spills, methane-triggered exploding water walls, fires and out-of-control flaring, animal deaths and human illness, as well as a host of other concerns associated with the industrialization of their rural community.

In a small town in Wyoming, the EPA recently found benzene, metals, naphthalene, phenols and methane in wells and groundwater which they say could be linked to gas development in the area, though the government has not yet determined the cause. ProPublica, which has reported extensively on the environmental cost of natural gas in an ongoing series, writes that the federal government has warned residents “not to drink their water, and to use fans and ventilation when showering or washing clothes in order to avoid the risk of an explosion.” Wyoming will soon become the first state to require companies to divulge what chemicals are in the water they’re pumping undergound.

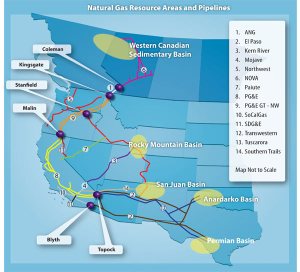

California’s own natural gas pipeline system is connected to the gas basin in Wyoming and many others, as illustrated on the map below. The Sunshine State only gets 13.5% of its natural gas from within its own state boundaries; the rest comes from neighbors in the southwest and parts of the Rockies and Canada. California is, in fact, the second largest consumer of natural gas after Texas.

Courtesy of the California Energy Commission

Pacific Gas & Electric, which operates the pipeline that exploded on Thursday in San Bruno, is sixth largest gas utility by sales volume in the country. The company immediately released a statement expressing its condolences to the community. “Though a cause has yet to be determined, we know what that a PG&E gas transmission line was ruptured,” the statement said. It went on to say that if the explosion was found to be the cause of the fires, it would take full responsibility. “The right thing is we will be accountable,” PG&E president Chris Johns told reporters that night. If that’s the way events unfold, it would be a welcome gesture, not only to the people affected in San Bruno, but to people around the country who are weary of energy companies unwilling to own up.