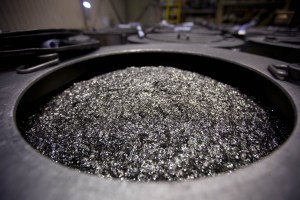

Annealed neodymium iron boron magnets at a factory in Tianjin, China.

Last month, after China and Japan locked horns over Tokyo’s arrest of a Chinese fishing captain whose boat collided with the Japanese Coast Guard, shipments of rare earths from China to Japan started to dry up at over 30 different Japanese companies. Since then, Beijing has stuck to its story – that the there is no official export ban in place and that any disruption to Japan has been market driven. Meanwhile, Japan and the U.S. are considering filing an embargo case over the matter to the WTO, as Bryan wrote about here last week.

Rare earths are a collection of 17 not-so-rare elements used to manufacture different parts of hybrid cars, mobile phones, missiles and wind turbines. They’re used in the glossy screen on your flat screen and your iPad — technologies that weren’t exactly a big deal 20 years ago when China got into the business. As other global players gradually left the dirty, expensive industry, China came to produce over 90% of the current global market of the minerals, which, according to the WTO, has grown at an annual rate of about 8% to 11% over the last decade, spiking in the last year. Many in the U.S., as the New York Times wrote last week, were already unhappy about China’s policy on rare earths since 2006 when Beijing imposed quotas and taxes on their export. Now they’re really unhappy.

For many, the shipment cuts to Japan, the world’s largest rare-earth importer, has spelled opportunity. Japanese companies are already looking into new mining opportunities in Mongolia and Kazahkstan. On Saturday, Germany extended a hand and said Berlin would team up with Tokyo to look for new rare earth production opportunities in other places where the minerals are found, like Namibia, Mongolia and the U.S. (They are actually pretty abundant, as it turns out.) Earlier this year, Colorado-based Molycorp Minerals LLC also announced plans to start back up with its operations at Mountain Pass mine, once the largest producer of rare earths, which closed up shop in 2002 after China started offering a cheaper product.

Those mining initiatives are piggybacking on other recent efforts to find alternatives to China’s monopoly. A story posted last week in Technology Review also details various projects in Japan and the U.S. to find new materials to replace or decrease the need for rare earths. Tesla Motors, for instance, is using electromagnets in its Roaster, as opposed to the more common permanent rare-earth magnets. Hitachi and BMW are making similar moves to get out from under China’s thumb. But, the article points out, most of these, including several government-backed research projects in the U.S., are years off from completion.

And as one Japanese engineering professor pointed out to the WSJ, all these investments would probably be for naught if China decides to open the floodgates again.

“The only real solution to the problem is to buy new mining rights overseas,” said Toru Okabe, an engineering professor specializing in rare metals at the University of Tokyo. “But mines outside of China don’t have cost-competitiveness. If China begins to flood the market with cheap supplies again, they wouldn’t stand the competition.”