Some time late in 2011—at least according to the people-crunchers at the U.N. Population Reference Bureau—humanity will reach a new demographic milestone with the birth of the 7th billion living person. (As a measure of just how fast global population is growing, the 6th billionth living person—Bosnian Adnan Nevic—is only 11.) You can expect the event to be marked by the usual Malthusian worries—can the planet Earth really support 7 billion people, especially with the population expected to top 9 billion by mid-century? With some 1.5 billion people already living on less than $1.25 a day, nearly 1 billion people hungry and the natural world already heavily damaged, are we on the path to destruction?

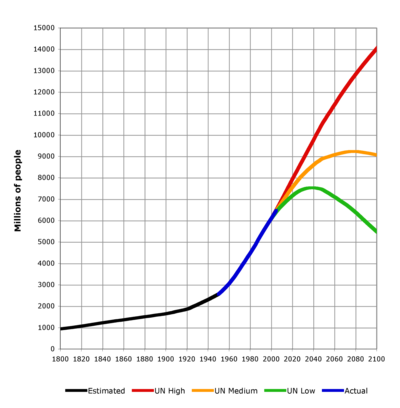

That’s the question the environment writer Robert Kunzig tackles in a cover story on population for National Geographic magazine. (I’ll excerpt a bit below, but it’s a great piece and worth reading in its entirety—in fact, consider picking up the issue, which tackles the 7 billion question with photos, articles and graphics.) Kunzig notes that global population has grown astoundingly fast during most of our lifetimes—while it took all of human history to around 1800 for the global population to reach 1 billion (a little Black Death here and there didn’t help), it will take a little more than 50 years for the world’s numbers to grow from 3 billion to 7 billion. A U.N. graph shows how fast population has grown, and where it might be headed:

That rapid increase is due to the demographic transition—and on the surface, it’s a sign of human progress. In the past, high fertility rates were the norm around the world, as women had to have large number of children to ensure that at least a few them would survive into adulthood. (That’s often still the case in extremely poor, heavily rural countries like Niger, where the average woman has seven children.) Eventually, though, child mortality declined thanks to advances in medicine and sanitation. As women adjusted to the new reality—and as families moved from farms to cities, where additional children were more of an economic burden than a boon—the fertility rate dropped, but that took a generation or so, and in the meantime population exploded. (Suddenly there were lots more surviving children who could then go and reproduce themselves.) The U.S., Europe and other rich countries have already gone through the transition—in most well-off countries fertility is around or even well below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman—and it’s begun to happen in all but the poorest developing countries as well. (China, thanks to the one-child policy, put itself through an accelerated demographic transition.) But the transition will take a while to play itself out, and global population will keep growing rapidly, albeit unevenly—for the next several decades, eventually reaching a level as high as nearly 11 billion or 8 billion by 2050, depending on how fertility rates change in the years ahead.

That rapid increase is due to the demographic transition—and on the surface, it’s a sign of human progress. In the past, high fertility rates were the norm around the world, as women had to have large number of children to ensure that at least a few them would survive into adulthood. (That’s often still the case in extremely poor, heavily rural countries like Niger, where the average woman has seven children.) Eventually, though, child mortality declined thanks to advances in medicine and sanitation. As women adjusted to the new reality—and as families moved from farms to cities, where additional children were more of an economic burden than a boon—the fertility rate dropped, but that took a generation or so, and in the meantime population exploded. (Suddenly there were lots more surviving children who could then go and reproduce themselves.) The U.S., Europe and other rich countries have already gone through the transition—in most well-off countries fertility is around or even well below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman—and it’s begun to happen in all but the poorest developing countries as well. (China, thanks to the one-child policy, put itself through an accelerated demographic transition.) But the transition will take a while to play itself out, and global population will keep growing rapidly, albeit unevenly—for the next several decades, eventually reaching a level as high as nearly 11 billion or 8 billion by 2050, depending on how fertility rates change in the years ahead.

Either way that seems to be a lot of people—and most of them will be born in poor developing nations, to parents already struggling to support themselves. If you’ve ever visited the urban slums outside growing megacities like Bombay or Lagos you might wonder how they could take any more people—yet they’ll continue to proliferate like bacterial cultures. Those teeming slums seem to provoke a visceral disgust among the thinkers who worry most about population—like Paul Ehrlich, the author of The Population Bomb, whom Kunzig quotes:

I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi a couple of years ago… The temperature was well over 100, and the air was a haze of dust and smoke. The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.

As Kunzig notes, that was written in 1966, when India only had 500 million people—today it has 1.2 billion, and it is projected to have over 1.7 billion by mid-century, which would make it the most heavily populated nation on Earth. But the question isn’t whether we will literally have enough space for more people—Kunzig points out that if 9 billion people were spread out around the habitable parts of the planet, the entire Earth would still have only half the population density of France. The fear—from Malthus to Ehrlich—is that we won’t be able to support ourselves, that there won’t be enough food, water or energy to go around, as Kunzig wonders:

Many people are justifiably worried that Malthus will finally be proved right on a global scale—that the planet won’t be able to feed nine billion people. Lester Brown, founder of Worldwatch Institute and now head of the Earth Policy Institute in Washington, believes food shortages could cause a collapse of global civilization. Human beings are living off natural capital, Brown argues, eroding soil and depleting groundwater faster than they can be replenished. All of that will soon be cramping food production. Brown’s Plan B to save civilization would put the whole world on a wartime footing, like the U.S. after Pearl Harbor, to stabilize climate and repair the ecological damage. “Filling the family planning gap may be the most urgent item on the global agenda,” he writes, so if we don’t hold the world’s population to eight billion by reducing fertility, the death rate may increase instead.

Eight billion corresponds to the UN’s lowest projection for 2050. In that optimistic scenario, Bangladesh has a fertility rate of 1.35 in 2050, but it still has 25 million more people than it does today. Rwanda’s fertility rate also falls below the replacement level, but its population still rises to well over twice what it was before the genocide. If that’s the optimistic scenario, one might argue, the future is indeed bleak.

I wrote earlier this week about the debate between Malthusians and Cornucopians—the economists who believe that human ingenuity, responding to human need, always prevails to find new resources to match rising populations. It’s an open question for the future, though so far the Cornucopians have been proven right. It’s worth noting that while we worry about the effects of overpopulation in the future, humanity was far worse off by every material standard in the centuries before the Industrial Revolution, when the global population was a fraction of what it is today. As Kunzig writes, the future of humanity—and of the planet we live on—will have less to do with absolute numbers that it will with how we choose to live:

For centuries population pessimists have hurled apocalyptic warnings at the congenital optimists, who believe in their bones that humanity will find ways to cope and even improve its lot. History, on the whole, has so far favored the optimists, but history is no certain guide to the future. Neither is science. It cannot predict the outcome of People v. Planet, because all the facts of the case—how many of us there will be and how we will live—depend on choices we have yet to make and ideas we have yet to have. We may, for example, says [population biologist Joel] Cohen, “see to it that all children are nourished well enough to learn in school and are educated well enough to solve the problems they will face as adults.” That would change the future significantly.

Indeed, growing populations won’t be the only demographic challenge the world faces in the decades to come. Remember how I said that population was growing globally but unevenly? Even as a country like India will likely need to cope with 500 million new people between now and mid-century, most rich nations—where the fertility rate is below replacement level and people live longer and longer—will need to cope with extreme aging. As the 2010 World Population fact sheet shows (download a PDF here), in Japan, Italy and Germany there are already only 3 working people to support every 1 pensioner. Compare that to sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, where the ratio is closer to 25 to 1. That disparity will only grow in the future, exacerbating budget headaches and skewing economies. In the U.S., for example, spending on Social Security and Medicare is expected to rise from 8.4% of GDP today to 14.5% by mid-century.

So here’s the planet we could have in 2050: an overpopulated, overstressed developing world and an aging, economically stagnant developed world, with inequality even larger than it is today. Is there any way to escape that fate? While development and education will be incredibly important (especially for women—literacy is one of the best ways to reduce fertility), the answer may end up being immigration. Think about it—in the future the developed world will lack young workers, and the developing world will have an excess of that resource. Immigration could be a way to balance demographics and economics—alleviating population pressure in the poorer parts of the world while jump starting aging developed nations. The U.S. already does this—immigration will provide most of American population growth. It would be a radical solution, given the political resistance to increased immigration in much of the rich world. (If you think it’s a hot topic in the U.S., try Japan, which steadfastly resists assimilating foreigners, despite the dire threat posed by an aging population.) But it might be the only way to save our overpopulated planet.

More from TIME on population: