An evening view of Hong Kong's business district shrouded under smog on March 22, 2010 in Hong Kong. Due to record-high pollution levels, the government warned people to stay indoors.

Following alarming reports of thousands of annual deaths from pollution in Hong Kong and the city’s promise to reach World Health Organization standards by 2014, air pollution and clean energy have been infectious topics in Hong Kong this year. With an air quality objective more than 25 years old, government response has arguably been slow to act, but there have been swift and ample efforts from local academics, activists and engineers to get the first-class city on track to meet first-rate air quality standards.

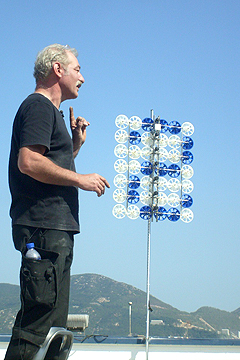

One Hong Kong-based inventor, Lucien Gambarota, is leading the way. Since the age of 12, the French-born Italian has been making a name for himself as a trailblazing engineer. Forty years since his first invention — an underwater breathing machine — Gambarota is living in Hong Kong with roughly 300 innovations under his belt. Sensing that energy would be an issue for future generations, Gambarota began focusing his electric zeal on conservation and renewable projects about a decade ago. He’s created everything from a welcome mat that powers a light bulb to large-scale projects, such as a wave machine that harnesses energy from the ocean.

(MORE: Political Pollution: How Bad Air is Slowly Changing China)

With Hong Kong’s dearth of natural resources, limited amount of land, and whole lot of water, Gambarota says he thought his wave machine made sense for the coastal city. His designs and prototypes prompted interest from the government and local academics, but before long, the inventor ran out of funding. “I did the only thing I knew how to do,” Gambarota tells TIME. “I decided to raise money by inventing something else.” Constantly juggling four to five innovations simultaneously, the scientist looked to the sky for a solution.

In 2007, Gambarota partnered with Dennis Leung, a professor at Hong Kong University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, and Michael Leung, now the Director of the Ability R&D Energy Research Centre of City University, to develop a micro-wind turbine intended for urban environments. The trio presented its technology at a press conference that year, and within three days, had orders from all over the world. They weren’t prepared for the interest: “We just had a few prototypes, we didn’t have a manufacturing facility or anything,” Gambarota says. But within three months, they managed to set up an entire business, complete with molds, a factory and international shipping partners.

Gambarota’s company, Motorwave Limited, made its first shipment in June of 2007. Since then, the 10-in.-wide, colorful plastic turbines have shipped to 45 countries, with more than 2,000 installations internationally. They have been strewn across European skylines, American silos, Hong Kong facades — they’re even gracing ferry boats on the way to Macau casinos. Part of the reason the tiny turbines have been so popular is thanks to their lightweight, colorful design and affordable price — running at about $1,000 per dozen.

(MORE: The 10 Most Air-Polluted Cities in the World)

Courtesy of Lucien Gambarota

The electricity generated by a micro-wind turbine is transmitted and stored in a battery, that can later be used to power home electrical appliances such as lights, LCD monitors and TV sets. For example, it takes roughly 120 micro-turbines to power the spotlight atop Hong Kong’s City Hall. And even better, commercial enterprises, schools, and government buildings can design the turbines to look like logos or billboards. They also work at incredibly low wind speeds. Whereas conventional turbines are designed to work at a start speed of about 5 to 7 meters-per-second winds, these mini counterparts can start with winds as slow as 1 meter per second, which basically translates to a leisurely stroll, or a breeze—one you can’t feel.

Though Hong Kong has also been using renewable energy to heat its swimming pools and power its weather stations for more than 20 years, the city’s goals for renewable potential are not exactly ambitious. The Energy Information Administration estimates that electricity generated from wind power will account for 6% of total electricity generated worldwide in 2020. In comparison, Hong Kong has one active wind turbine on Lamma Island, producing much less than 1% of its total energy generation. The Hong Kong government aims to increase electricity from renewable energy from 1 to 2% in 2012 to a whopping 3% by 2022. To put that into perspective: Across the border, China intends for wind, solar and biomass energy to represent 8% of its electricity generation capacity by 2020, France is aiming for 23%, and Germany for 35%.

Gambarota certainly intends to steer Hong Kong away from coal toward renewable sources with his inventions, but he says renewable energy isn’t the city’s No. 1 priority at this point. First, Hong Kong must address energy efficiency. “When you have a building that is consuming 70% or 80% more than it should, you are just going to waste energy, regardless of the source,” Gambarata says. “First we must retrofit, then we can think more seriously about renewables.” Instead, he says, engineers, policy makers, commercial enterprises and everyday citizens should try to increase the efficiency of everyday consumption, such as lighting, transportation and especially, air conditioning, which accounts for one-third of the city’s total electricity usage based on the Hong Kong Energy End-Use Data 2011. If architects and urban planners could decrease the energy generation of these basic, daily amenities, then they’d finally gain an upper hand in the war against pollution.

(PHOTOS: After Fukushima: Images from Japan, One Year Later)