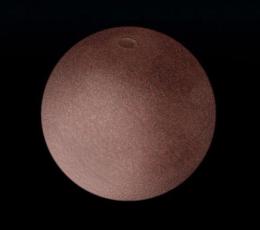

An artist's rendering of Makemake

The furor surrounding Pluto’s demotion from planet to dwarf planet back in 2006 still hasn’t gone away, but all the noise — much of it coming from disgruntled schoolchildren — has obscured the genuinely exciting science underlying that decision. Astronomers began to understand during the 1990s and 2000s that Pluto was just the most visible member of the Kuiper Belt, a vast ring of icy, rocky debris circling the solar system that was left from the time the sun and everything that orbits it formed. Little, planet-like bodies called Trans-Neptunian Objects (or TNOs) with names like Quaoar, Sedna and Haumea joined the sun’s family over that time, and when a world named Eris was found to be more or less the same size as Pluto, it became clear that scientists would have to either cut the number of planets off at eight or eventually start counting up into the dozens, at least.

(MORE: Get Pluto Out of Here!)

Much more important, though, is the fact that planetary scientists can study some of these tiny bodies despite their multibillion-mile distance from Earth. The latest to come under scrutiny: Makemake (named after the creator god of the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island), which lies about 4.6 billion miles (7.4 billion km) from Earth. Writing in Nature, Jose Ortiz of Spain’s Andalusian Institute of Astrophysics, along with a long list of colleagues, reports that unlike Pluto, Makemake has no global atmosphere, but it may have atmospheric patches that hover over parts of its surface. “It is,” says Ortiz, “at least a theoretical possibility.”

Actually, he’s being partly humble. Makemake may or may not have patches of atmosphere, but Ortiz and his team know that it doesn’t have a complete one because they were able to watch as the world passed directly in front of a background star named NOMAD 1181-0235723. If the atmosphere had been there, the star would have faded out. Instead, it winked out abruptly — and winked back in when Makemake emerged from the other side about a minute later.

(Photos: Window on Infinity: Pictures from Space)

This sounds pretty simple, but predicting that Makemake would pass in front of this particular unnamed star, in what’s known as an occultation, wasn’t. From Earth, Makemake appears to be about the size of a quarter sitting 30 miles (48 km) away, and neither the TNO’s orbit nor the star’s position was known with great accuracy. When the astronomers found what seemed to be a good candidate star more or less in Makemake’s path, they calculated whether an occultation was likely, then recalculated over and over as the TNO inched toward the star. In some cases, the encounter never did happen, but on April 23, 2011, the scientists hit pay dirt.

The abrupt off-on of starlight told them part of what they needed to know about Makemake’s atmosphere: it’s not complete. Evidence of its possible patchiness was gathered through remote observations by the space-based Herschel and Spitzer infrared telescopes. They showed that the world has spots of brighter and darker terrain, and because they reflect less light, the dark regions are significantly warmer — warm enough, says Ortiz, that methane ice on the surface would be heated to a gaseous state, forming patches of atmosphere.

(MORE: Why Pluto Now Has Five Moons but Is Still Not a Planet)

In fact, Ortiz says, there might even be some direct evidence for such patches. The occultation was spotted by seven telescopes that viewed the passage from slightly different angles. In some of the telescopes, there was a hint that the starlight didn’t wink out quite as abruptly as in the others, suggesting that a patch of atmosphere just happened to be lined up with the star. But, adds Ortiz, “we cannot completely rule out an instrumental problem.”

Besides confirming that Makemake has (mostly) no atmosphere, the timing of the passage revealed that the tiny world is a slightly squashed sphere about 888 miles (1,430 km) across in one direction and 933 miles (1,502 km) in the other — about half as large as Pluto.

More occultations would nail these numbers down even more precisely, and might help settle the patchy-atmosphere question as well. Unfortunately, there don’t seem to be any new such sightings in Makemake’s future — although, says Ortiz, “we don’t make predictions more than a year in advance because of the orbital uncertainties in TNOs.”

Sedna, on the other hand, which lies about 10 times further away than Makemake, “looks particularly promising for a stellar occultation,” Ortiz says. Time and date still to be announced.

MORE: NASA’s Cosmic Children: Taking Stock of a Growing Interplanetary Fleet