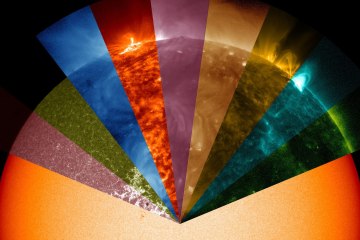

Every summer about this time of year, the Earth passes through the orbital path of the Swift-Tuttle comet. That might sound a little alarming, but don’t worry—the closest we’re likely to come to the comet itself will be 1 million miles, and astronomers calculate that won’t be until 3044. (Still, a near miss by cosmic standards.) But bits and pieces that have broken off from the tail of the comet do collide with the Earth’s atmosphere, creating one of the most reliable and spectacular star shows of the year: the Perseid meteor shower, so called because the meteors, as they streak across the sky, seem to originate from the constellation Perseus.

This year the shower was intense, with as many as 100 separate shooting stars—cosmic matter burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere—tearing across the sky per minute. (An average meteor shower might have as few as one shooting stars per minute.) The Perseid meteor shower has been observed for some 2,000 years. Catholics used to call the shower the “tears of St. Lawrence,” since the martyred saint’s feast day of Aug. 10 often coincided with the show.

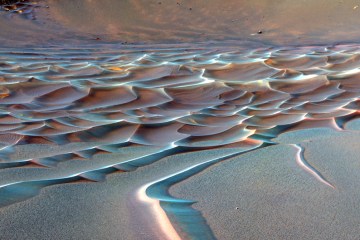

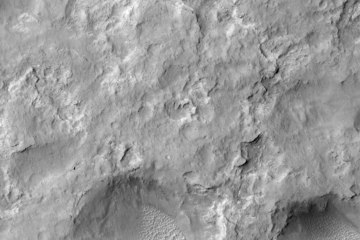

2013’s meteor shower has been particularly impressive because the lunar calendar ensured that the moon had all but disappeared from the sky during peak viewing hours. Of course, those of us who live in cities and near other sources of light pollution won’t be able to make out the full power of the Perseid shower—assuming you can stay up late enough to see it. But the images that follow give you a taste of what you might be missing.