If you had your druthers during Christmas week 1968, you’d have wanted to get as far away from Earth as possible. The entire planet was a mess—southeast Asia was in flames, Czechoslovakia was living under a Soviet crackdown, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King had been murdered and cities across the country had been torn by rioting.

As it happened, three men out of the 3.5 billion human beings then at large did have the chance to get out of Dodge, and so, on the morning of December 21, the crew of Apollo 8—Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders—climbed atop their Saturn V rocket and set out for humanity’s first manned mission to orbit the moon. For a trip that began with nothing short of an act of chemical violence—7.5 million lbs (3.4 million kg) of thrust exploding out of the bottom of a 36-story rocket, accelerating the crew to an escape velocity of 25,000 mph (40,000 k/h)—the actual moonward coast was a rather lazy thing.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dE-vOscpiNc&w=560&h=315]

For three days, the astronauts would drift away from the planet, their speed steadily slowing as the Earth tugged inexorably back on them. Finally, 80% of the way to the moon, lunar gravity would take over, speeding them up and pulling them in. Until the critical moment when they’d fire their engine to ease themselves into lunar orbit, they had comparatively little to do, and so, on the morning of Dec. 22, when they were 104,000 mi. (167,000 km) from home, Houston radioed up with the day’s headlines.

“Let me know when it gets to be breakfast time,” said the Capsule Communicator (Capcom) in Mission Control. “I’ve got a newspaper to read up to you.”

“Good idea,” said Borman. “We never did get the news.”

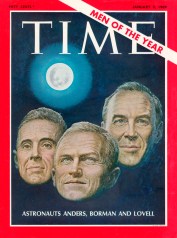

TIME’s Jan. 3, 1969 issue, showing Men of the Year Apollo 8 astronauts William A. Anders, Frank Borman and Jim Lovell.

“You are the news,” the Capcom answered. “The flight to the moon is occupying prime space on both newspaper and television. In other news, eleven GIs that have been detained five months in Cambodia were released yesterday and will make it home for Christmas. David Eisenhower and Julie Nixon were married yesterday in New York; he was described as ‘nervous.’ The Browns took Dallas apart yesterday 31 to 20, and we’re sort of curious: Who do you like today, Baltimore or Minnesota?”

“Baltimore,” Lovell answered. (History records that he was right: the Colts beat the Vikings 24 to 14.)

“Mighty nice view from out here,” Borman said peacefully.

That the men in space and on the ground could chatter so idly was a mark of both their surpassing cool—temperamental types washed out long before they ever saw the inside of a spacecraft or a console in Mission Control—and of the fact that the sheer, improbable novelty of what they were doing made it almost impossible to react any other way. If you’ve never seen the moon up close—never watched it make the transition from a disk in a telescope to an arc of horizon far, far too large to fit in your window—you have no idea how gobsmacked by the experience you soon will be and so you approach it with something of a show-me shrug.

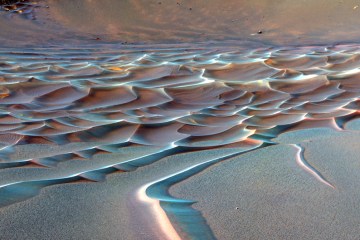

But another fact that history recorded—one vastly more important than the score of a football game—was that it was not the sight of the moon growing in the astronaut’s window that struck people most, but the sight of the Earth shrinking. For all of the millions of years humans and pre-humans had existed, the Earth was always the thing underfoot, the thing all around, the thing that, even from orbit, could never be seen whole, never be reduced to the blue, marbleized Christmas ornament that it is—a tiny, fragile, sphere, suspended in the middle of nothing at all, with a billion billion creatures depending on it for life.

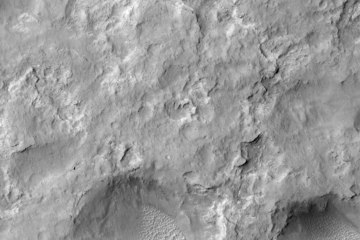

And then, during Christmas week 1968, the perspective at last changed. The astronauts orbited the moon on Christmas Eve, pointed their TV camera at the plaster of Paris lunar wasteland crawling slowly by beneath their spacecraft, and read Genesis to a global television audience watching the grainy images and listening to the staticky voices coming to them from nearly a quarter of a million miles away. A few atheist groups grumbled—something about church and state and a government-funded mission and on and on. But the rest of the world—the whole angry, brawling, bloody, warring world—stopped and watched and contemplated and prayed and sometimes wept. Something about swords and ploughshares, it seemed for at least a moment.

And even that—even the sublime lyric poetry of three explorers gift-wrapping the moon on Christmas eve—was not the most indelibly affecting image of the mission. It was a single picture the crew took earlier that morning, during their fourth orbit of the moon, with no TV camera on and nobody from the ground watching at all. It was Earthrise—the iconic Earthrise—the living, blue planet rising over the dead lunar horizon. It’s the picture that was credited with starting the environmental movement, that has been on postage stamps and t-shirts, album covers and coffee mugs, that has been used as a hopeful symbol of global unity at peace rallies and health conferences, on Christmas cards and in works of art.

As a newly released NASA video reveals, even the astronauts were not entirely sure of what they had just photographed—but they had a pretty good idea. “My opinion at the time was that I thought it would be a great picture,” Lovell said today in a conversation from his home in Lake Forest, Ill. “But I didn’t comprehend that, in today’s language, it would go viral—that it would be the capstone and message of the mission.”

Besides, the three men had other things on their minds throughout the mission, especially when they were actually in lunar orbit: “You have to remember, we had become a satellite of the moon,” Lovell says. “And in the back of our minds was always the question ‘Will our engine restart when we need it to?'” The engine did restart, and as the spacecraft rounded the far side of the moon after the tenth and final orbit and emerged from blackout, Lovell broadcast that good news to the world. “Houston,” he said, “please be informed there is a Santa Claus.”

It was only in the days after Christmas, when the crew had safely splashed down in the Pacific, that the Earthrise film could be carried to a lab, hand-developed, hand printed, hung, dried and then finally, fully revealed for the extraordinary thing it turned out to be: It was nothing more or less than a photo of home—and it was like nothing the human species had ever seen before.

Borman, Lovell and Anders are all well, all thriving, all in their 80s today, celebrating their 45th Christmas since their epic trip. They are, like the rest of us—7 billion of us these days—mere creatures of the Earth again. But 45 Christmases ago they weren’t—and briefly, by exquisite extension, neither were we.