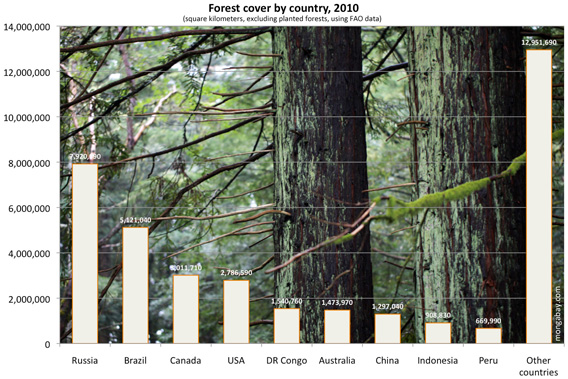

The story of the world’s forests is usually a depressing one. Tropical rain forests are under pressure in South America, Asia and Africa, threatening habitat for countless species and adding billions of tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere every year. But while the headlines can be scary, the reality is that the world may be close to turning a corner on deforestation—a change that could pay off for wildlife and the climate. According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), there were 4.032 billion hectares of forest standing in the world in 2010. That’s down slightly from 2000, but the good news is that the rate of overall forest loss has slowed considerably, dropping from 8.3 million hectares lost a year in the 1990s to 5.2 million hectares a year, thanks in part to significant reforestation taking place throughout much of Asia. A graphic from the forest site Mongabay.com shows where the trees are:

2011 could be the year the world finally stops losing the fight against deforestation. On February 2 the U.N. launched the International Year of Forests, beginning a series of events meant to raise awareness about the vital importance of forests and generate support for sustainable forestry practices. At December’s U.N. climate summit in the Mexican city of Cancun, governments took the first concrete steps towards creating a system for avoided deforestation, or REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation), which would allow companies and countries to claim carbon credits for maintaining trees. But at the same time, record high food prices could reverse all of that progress, if farmers around the world choose to clear forest to make room for more crops. “In my view, 2011 is going to be the critical year,” says Frances Seymour, the director-general of the Center for International Forestry Research. “This is the year we’ll find out whether we’ll be successful or not.”

First the good news. Most environmentalists believe that REDD offers the best way to generate the billions in finding needed to finally halt deforestation in the tropics, where forests and jungles support a wealth of biodiversity. Right now, a forest only has monetary value when it’s been cleared for farming and sold for logging. Simple economic pressures explain why we’ve already lost so much forest in the world’s poorest countries. But REDD changes that equation. By measuring and creating a market for the billions of tons of carbon contained within trees, REDD could make it economically worthwhile to keep forests standings, by letting tropical countries essentially sell the carbon but keep the trees. Greed could save forests, instead of destroying them.

But for REDD to ever work at scale beyond a few small pilot projects, it would need to be tied to an international climate deal. For most of 2010, in the wake of the Copenhagen summit’s collapse and Congress’s failure to pass a carbon cap, that seemed impossible. Because a carbon market is needed support avoided deforestation, no climate deal, no REDD. Yet at the end of 2010 diplomats in Cancun managed to pull together the beginnings of a global climate agreement that crucially included a framework for REDD funding. That success has paved the way for funders like the Norwegian government, which has spent hundreds of millions of dollars to begin setting up REDD pilot projects in Brazil and most recently Indonesia, which has long suffered some of the worst deforestation in the world. At the UN Forest Forum in New York last week, Rwanda even pledged to restore its degraded landscapes from border-to-border—with the help of REDD funding. “If REDD can really get going in Indonesia, that could be a game changer,” says Seymour.

Still, all this progress could be lost if forests end up pitted against food. According to the FAO, global food prices in February were higher than they have even been before—breaking a record that was only set in January. With demand from the developing world—especially for meat, which requires significant amounts of grain—likely to keep growing, and bad weather in major farming nations keeping yields down, food prices aren’t likely to fall any time soon. At the same time, the decades of steady improvement that has allowed farmers to get more food out of ever acre has plateaued. If the world is going to get more food, it’s going to need to farm more land—and that’s often when forests start getting clear cut. “We’re looking at a perfect storm,” says Seymour. “Farming could be a major driver in forest loss.”

Deforestation isn’t an automatic consequence of high food prices though. Instead of cutting down virgin forest, farmers can look to expand farming to degraded land. Over the longer term, better investment in agricultural research—which has lagged in recent years—can lead to better yields and higher efficiency, reducing the need for more land. And agroforestry can actually combine trees and farming, to the benefit of both. In Africa a growing number of farmers are actually intercropping trees with their farmland, which can cheaply boost nutrients in their soil—certain species of trees actually fix nitrogen, reducing the need for fertilizer—and provide a ready supply of firewood. “Everyone has something to gain from this,” says Dennis Garrity, the director-general of the Nairobi-based World Agroforestry Centre. “People just have to realize this can be done.” That’s the sort of creative thinking that will be needed to make 2011 the year deforestation really ends.