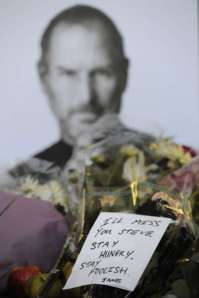

Carl Court—AFP

I missed the all-night, stop-the-presses TIME session last week that put together an amazing and entirely new issue to commemorate the death of Apple’s Steve Jobs. I don’t have much more to add, other than the fact that like so many other people, I found out the news on an Apple product and am writing this on another one. Outside TIME’s work, I suggest you check out Alexis Madrigal’s take at the Atlantic on why Jobs’s death has caused the kind of global grief you’d usually see from the passing of a religious figure:

Steve Jobs believed in more for everyone: more money for him and his shareholders, more power through personal technology for the people. He was the white wizard in the black turtleneck holding the forces of decline at bay. Apple enjoyed one of the greatest runs in the history of industry right into and through the teeth of the worst economic times since the Great Depression. Steve Jobs was hope backed by manufacturing and an empowering outlook on life, a child of the grooviness and bigthink of the 1970s married to the drive of the 1980s.

I’m an Apple addict, too. But I’d be remiss if I failed to note that the bright white facade of Jobs’s dream had a dark side as well, that in between his faultless designs and his legions of dedicated fans was the often harsh reality of globalized manufacturing, one that can be tainted in blood.

Many Apple products are manufactured by Foxconn, a Taiwan-based electronics company that maintains most of its factories in China. Many of their workers are Chinese migrants who’ve come to the city to take advantage of the country’s economic boom. But it’s not a pretty life—there have been frequent allegations of mistreatment at Foxconn over the past several years, and even the average life of a worker at such a high-pressure environment would be unimaginable to most of the people who actually buy and enjoy Apple products. They work for 10 hours or more a day, with a lunch hour and a couple of brief 10-minute breaks, standing on an assembly line and performing the same task over and over.

And then there are the suicides. News reports indicate that over 15 Foxconn workers have killed themselves over the past several years, and there’s some evidence that the intense pace of work needed to meet the world’s unquenchable thirst for new Apple products might have contributed to some of the deaths. In a great piece published earlier this year in Wired, Joel Johnson visited a Foxconn plant, asking himself whether his love of Apple products essentially made him complicit in the deaths of those workers and whether the entire idea of consumer electronics was somehow tainted by that fact:

Every last trifle we touch and consume, right down to the paper on which this magazine is printed or the screen on which it’s displayed, is not only ephemeral but in a real sense irreplaceable. Every consumer good has a cost not borne out by its price but instead falsely bolstered by a vanishing resource economy. We squander millions of years’ worth of stored energy, stored life, from our planet to make not only things that are critical to our survival and comfort but also things that simply satisfy our innate primate desire to possess. It’s this guilt that we attempt to assuage with the hope that our consumerist culture is making life better—for ourselves, of course, but also in some lesser way for those who cannot afford to buy everything we purchase, consume, or own.

It’s not that Foxconn is a Dickensian sweatshop—as Johnson notes, the suicide rate at those plants is lower than the national average in China, and significantly lower than the rate of suicides among American college students. And these workers aren’t slaves—they chose to leave the Chinese countryside for a life in the city, for the hope of something a little bit better. In a sense, they’re participating in the “more” that Madrigal identifies as Steve Jobs’s ultimate aim for everyone.

But only a little bit. There’s no getting around the uncomfortable fact that those factories, those suicides, don’t quite fit into Jobs’ unassailably brilliant vision—and yet, those iPhones and iPods and Macs wouldn’t exist without them. (Or at least, they wouldn’t be affordable and they wouldn’t be mass.) And I feel a little uncomfortable at all the hosannas over Jobs the genius, as if he simply imagined the iPhone from a room in Cupertino and so it was. To support one man’s ability to live a truly amazing life—to fulfill his dreams and fire our own—required the hard and mechanical labor of so many anonymous souls whom no one will commemorate when they pass.

Of course, we’re the ones who buy those products—and therefore much of the responsibility should lay with us. In an interview with the New York Times, the performance artist Mike Dailey—who is putting on the (extremely well-timed) one-man show The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs—noted that while we’ve begun to care more and more about where our food comes from, we show little concern for how our beloved electronics are made:

The situation we find ourselves in is not terribly different than it was for the organic food movement in the 1950s, an era when the idea that food should not be treated with pesticide was bizarre because people didn’t even understand why you wouldn’t want your food in a can. In other words the act of making people think about these issues is a revolutionary act because no one is talking about it.

As we rightly mourn the dream of Steve Jobs—a man who transformed multiple sectors of the economy—we should remember to look through the elegant design, all smooth edges and pure white, and into the guts that helped give it life.

Bryan Walsh is a senior writer at TIME. Find him on Twitter at @bryanrwalsh. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME